About

The Sustainable Biomass Program (SBP) is a private certification scheme developed by the bioenergy industry to address public and regulatory concerns over the sustainability of biomass fuels, specifically wood pellets and chips. SBP-certified pellets are traded globally at scale, primarily to serve European energy demand. Despite this growing reach and influence, the sustainability claims underpinning SBP certification remain under-scrutinized.

This research addresses this oversight by critically analyzing the core claims made by SBP, particularly those that present forest biomass as a climate-friendly alternative to fossil fuels. It examines SBP’s reliance on other certification mechanisms to validate biomass sourcing and exposes the weak foundations behind its assurances of carbon neutrality.

This report is co-published by SFOC, Global Environmental Forum, Mighty Earth, Biofuelwatch, and Biomass Action Network of the Environmental Paper Network.

Download report

Executive summary

Faced with pressure to meet climate commitments and reduce reliance on fossil fuels, many countries have turned to forest biomass as an alternative source of heat and electricity. Biomass now constitutes a significant portion of the energy mix in the European Union, United Kingdom, Japan, and South Korea. However, burning wood for energy accelerates the destruction of the world’s biodiverse and carbon-rich forests, which are already under severe pressure. Decades of research in climate and forest sciences have made it clear that large-scale biomass use exacerbates the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

In response to mounting criticism, governments have sought evidence that biomass they support is ‘sustainable’ and contributes to lowering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The biomass industry responded by creating the Sustainable Biomass Program (SBP) to assure that wood pellets and chips used for energy are sourced sustainably. However, SBP is a private certification scheme developed by the very industry it purports to regulate. It is backed by powerful market incentives in the form of government subsidies, not to restrain the industry, but to promote it. Evidence shows that this structural conflict of interest has resulted in weakened standards and superficial compliance mechanisms that encourage practices far removed from true sustainability.

Sustainable Biomass Program: Certifying the Unsustainable investigates the claims made by SBP through a review of its standards, policies, and procedures. This report finds that SBP’s portrayal of biomass as a climate-friendly alternative to fossil fuels is misleading on several grounds:

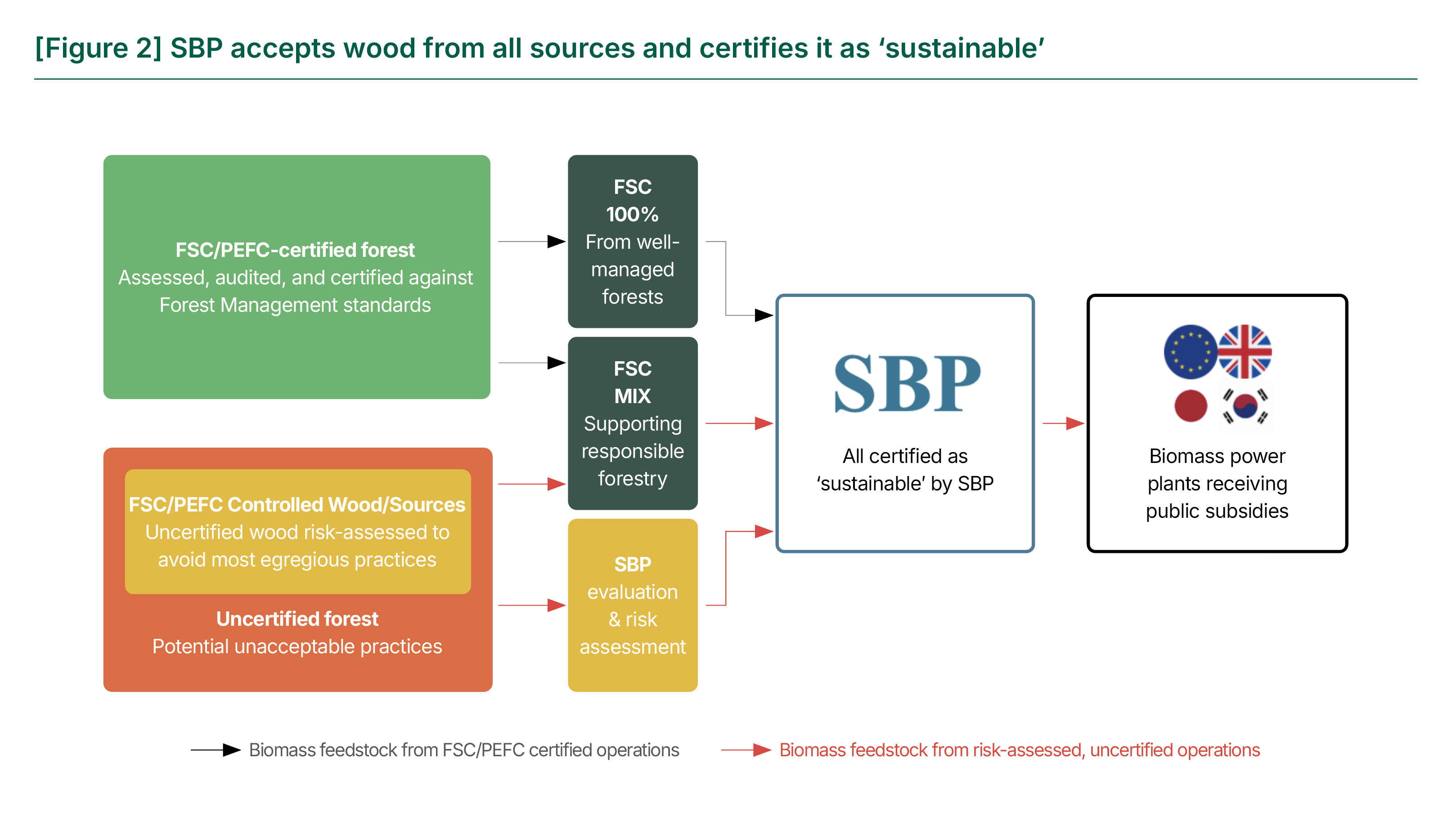

SBP certifies pellet mills and traders without field audits of forest management practices or direct engagement with logging companies. Unlike other forest certifications, SBP relies on desk-based Risk Assessments and broad screening tools that detect only illegal or grossly unacceptable sources, not genuine sustainability.

SBP misrepresents the credibility of other certification systems. It treats FSC “Controlled Wood” and PEFC “Controlled Sources” as if they were fully certified sources. In reality, these categories undergo only minimal risk assessment. SBP uses this lower-tier wood to label entire biomass supply chains, including wood from uncertified forests, as sustainable, effectively lowering the bar for what counts as ‘sustainable forest management’ (SFM).

SBP’s climate impact claims rely on flawed carbon accounting. The scheme assumes that emissions from burning wood are offset by forest regrowth over decades, ignoring the urgent emissions reductions required by 2030 to meet the Paris Agreement. SBP permits sourcing from areas with net carbon losses and uses national averages instead of site-level data, allowing companies to offset carbon-rich forest losses with regrowth in less carbon-dense areas.

SBP fails to mitigate smokestack emissions from burning biomass, deferring this responsibility to energy regulators. By ignoring the fact that biomass emits more CO₂ per unit of energy than fossil fuels, SBP enables operators to claim ‘carbon neutrality’. Current accounting methods fail to trace these emissions back to the land use sector, and the energy sector avoids bearing the cost of climate mitigation associated with biomass use.

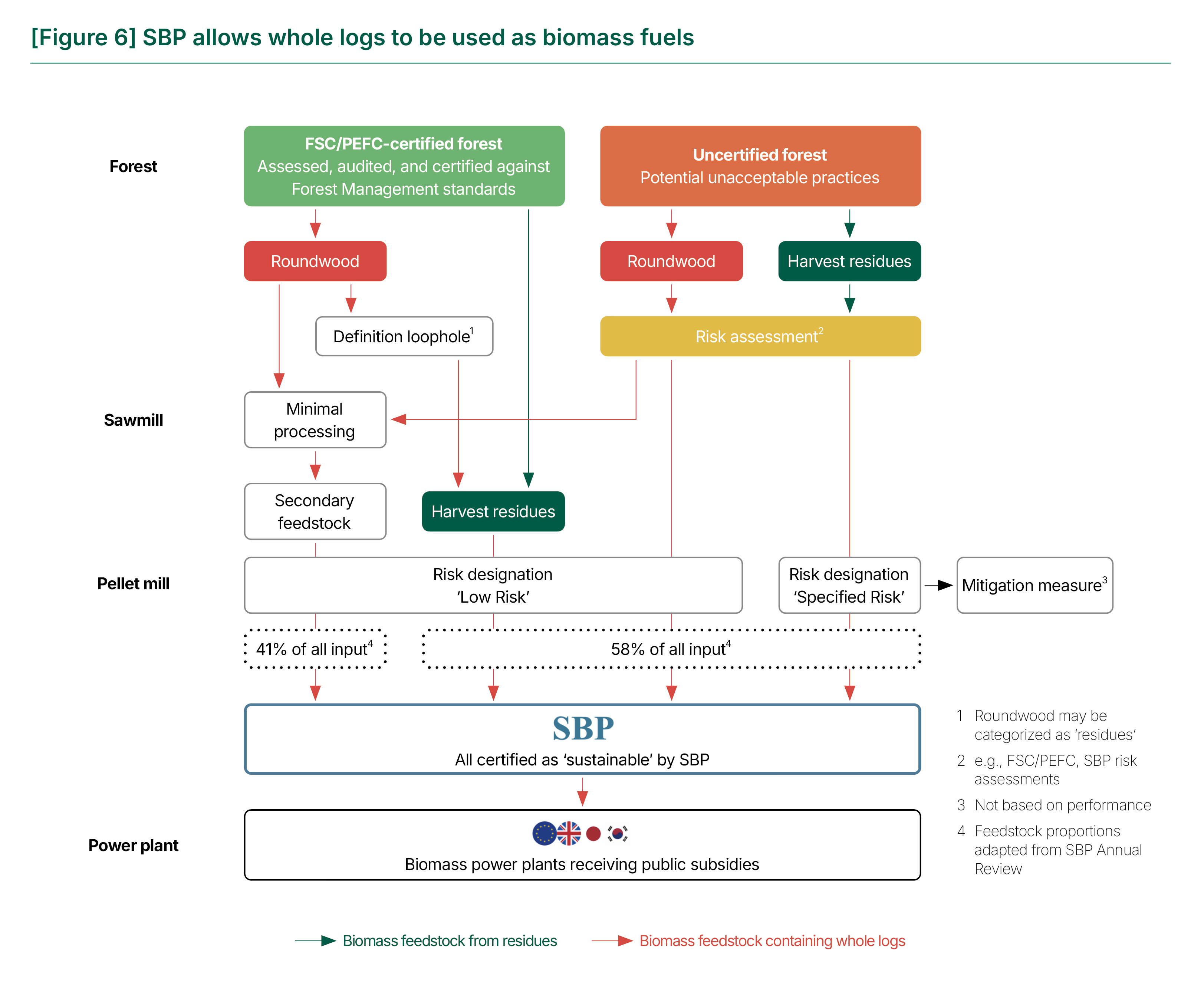

SBP treats ‘forest residues’ as low-risk by default, certifying them even when they originate from primary forests. The framework allows producers to categorize whole logs as residues or byproducts without meaningful oversight, masking the environmental damage of such sourcing.

SBP inadequately addresses Indigenous peoples’ rights. While it acknowledges the need for consultation, SBP still allows certification to proceed even when free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) has not been obtained, sidestepping the rights of Indigenous communities.

Benefiting from these systemic flaws, SBP offers a convenient mechanism for regulators and utilities to fulfill reporting requirements. Biomass producers can claim sustainability even when sourcing wood from uncertified forests, so long as it appears low-risk on paper. Neither the degradation of forests nor the emissions from burning biomass are properly accounted for, thus creating an accountability gap where no one assumes responsibility for the climate impacts. The case of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada—explored in Part 2 of this report—demonstrates how these systemic failures unfold on the ground.

Despite its name, SBP does not ensure sustainable sourcing of biomass fuels. It endorses industry practices that fall short of other sustainability certification systems and international SFM norms, while contributing to the perception among policymakers, investors, and the public that forest biomass is a renewable energy source. The reality is that the world is already extracting far too much from standing forests. Any additional pressure from exploitative bioeconomy schemes risks derailing global climate and biodiversity goals.

Burning our last remaining forests is not a climate solution, it is a dangerous distraction that narrows the path to a safer future. SBP, in turn, is not fit for purpose.

Recommendations

Governments: Reject forest biomass

Recognize large-scale biomass for what it is: a high-carbon, low-efficiency fuel. Burning wood emits more CO₂ per unit of energy than fossil fuels, and forest regrowth may take decades to centuries to repay this carbon debt, far beyond the timelines needed to meet climate targets.

Include combustion emissions in national GHG inventories. Excluding these emissions from carbon accounting is scientifically flawed and obscures the true climate impact of biomass energy.

Governments: Protect natural forests

Prohibit sourcing wood from primary forests and Intact Forest Landscapes (IFLs). Primary forests are irreplaceable reservoirs of carbon and biodiversity. Logging them undermines global climate and biodiversity goals.

Shift climate mitigation strategies away from a wood-based bioeconomy. Instead, focus on halting and reversing deforestation and forest degradation by 2030, in alignment with international biodiversity goals.

Governments: Reform subsidy and trade policy

End subsidies for forest biomass and exclude it from green finance criteria. The biomass industry is propped up by public incentives that distort markets and divert funds from genuinely clean energy solutions.

Mandate human rights and environmental due diligence in all international timber trade. Voluntary certification schemes like SBP are insufficient to prevent social and ecological harm.

Forest certification systems: Strengthen standards

Reform FSC and PEFC systems to prevent the misuse of Controlled Wood and risk-based assessments as stand-ins for full certification. These mechanisms are being exploited to greenwash unsustainable biomass supply chains.

Cease certifying wood pellets under current large-scale biomass models. Acknowledge that scaling biomass energy is incompatible with protecting forest integrity. The widespread reliance on mixed-label products undermines the credibility and mission of forest certification systems.

![[Webinar] International webinar on enhancing due diligence of forest risk commodities' supply chains in Asia](https://content.sfoc.tapahalab.com/images/research/sjGudme.jpg)

![[토론회] 한국형 녹색분류체계(K-Taxonomy), 무엇이 녹색경제활동인가](https://content.sfoc.tapahalab.com/images/research/bn8jdme.jpg)

![[Webinar] Palm Oil based Biofuels Policy and Socio-Environmental Impacts in Asia](https://content.sfoc.tapahalab.com/images/research/BOpldme.jpg)