COP30 has been dubbed the “implementation” and “adaptation” COP, citing Brazil’s determination to translate public promises and written commitments into concrete action. For South Korea, one of the world’s top 10 greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting countries, this year’s negotiations will be the testing grounds for a new administration facing demographic decline, the retreat of multilateralism, and an economy based on heavy industries under growing pressure to decarbonize in line with an increasingly unfeasible 2050 carbon neutrality goal.

Last time, we highlighted the key issues expected to arise during this year’s COP negotiations. In this second and final installment of Before Belém, we explore what COP30 means for, and asks of, South Korea.

NDCs and the “Implementation" COP

A key agenda item in this year’s negotiations is the submission of 2035 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), voluntary action plans designed to reduce national emissions and facilitate climate mitigation and adaptation. NDCs form the operational backbone of the 2015 Paris Agreement, under which 195 UN Member States have committed to limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. While not legally binding, NDCs are a key indicator in assessing countries’ commitment — and therefore global commitment — to climate action. These national plans are subject to a “ratchet mechanism” that since 2015 has called on countries to progressively strengthen climate commitments every five years, marking early 2025 as the deadline for the 3rd round of submissions.

Despite the February deadline, just days before COP30, only 74 countries have submitted 2035 NDCs. Even among submitted NDCs, progress on renewable energy expansion and efficiency gains has been overshadowed by them largely skirting the more politically challenging task of curtailing coal, oil and gas at the source. Most submissions fail to address the elephant in the room — continued fossil fuel extraction, production and use — with major emitters like the US, Canada and Australia collectively increasing oil and gas production by around 40% since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015.

While submitted NDCs detail plans for renewable energy expansion and efficiency gains, they largely skirt the more politically challenging task of curtailing coal, oil, and gas at the source. This gap has been given severe legal weight by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which ruled in July’s landmark advisory opinion that states failing to adequately respond to the climate crisis could be found in breach of international law. NDC content is among the criteria determining whether countries are doing their due diligence – and not addressing fossil fuel expansion could mean legal consequences.

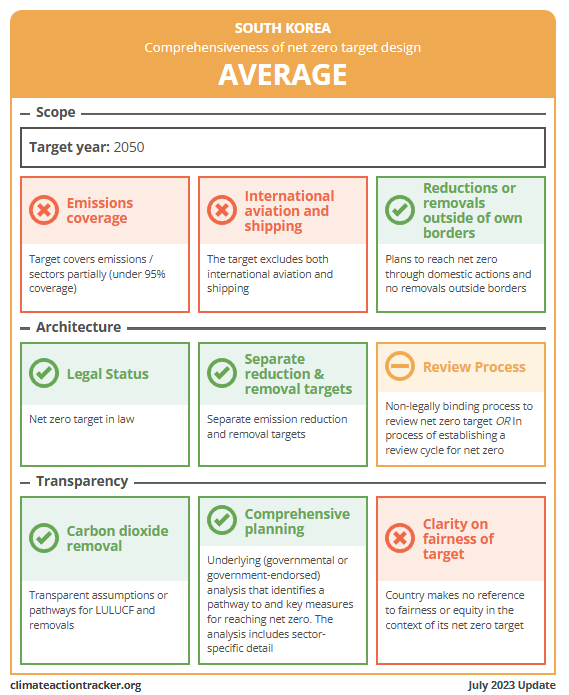

South Korea’s Last NDC: Pass or Fail?

In simple terms, South Korea’s 2035 NDC needs to pack a punch, especially if the country is to hit its ambitious 2050 carbon neutrality target.

Korea’s last NDC submission was in 2021, when the government committed to reducing national GHG emissions by 40% below 2018 levels (727.6 Mt CO₂eq) by 2030. Analysts deemed this target “highly insufficient”, with estimates indicating the country would need a GHG emissions reduction target of at least 54% to 68% to be in alignment with a 1.5°C pathway. Even the 40% target relies on a mix of domestic cuts, sinks from Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) sector, and international carbon credits, the latter of which have been criticized for lacking transparency and quality assurance.

In a landmark 2024 ruling, the Korean Constitutional Court found that the absence of specific reduction targets for the period from 2031 to 2049 effectively shifted an "excessive burden" onto future generations, violating their constitutional right to a clean environment. This successful lawsuit, combined with the ICJ Advisory Opinion, means Korea is under pressure to ensure its next NDC truly delivers or risk significant legal and political consequences.

What South Korea’s Fossil Fuel Addiction Means for a 2035 NDC

Korea’s 2021 NDC does not substantially address overseas emissions, a cause for serious concern given the ROK ranks second only to Canada in terms of global overseas fossil financing, pumping a whopping $10 billion per year into overseas projects. In comparison, money spent on renewable energy expansion was a measly $850 million, less than 8% of what was spent on fossil fuels.

To complicate matters further, last December, South Korea was one of only two countries loudly opposing the proposed expansion of the OECD Export Credit Arrangement’s restrictions on public financing for coal to all fossil fuels, earning widespread criticism. The ROK’s pro-fossil fuel financing stance is causing problems as far away as in Mozambique, where public and private agencies are backing onshore and offshore floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) projects rife with controversy surrounding environmental impacts, human rights violations and profit distribution.

Suffice it to say, South Korea’s new NDC has a lot of making up to do.

Towards a New NDC

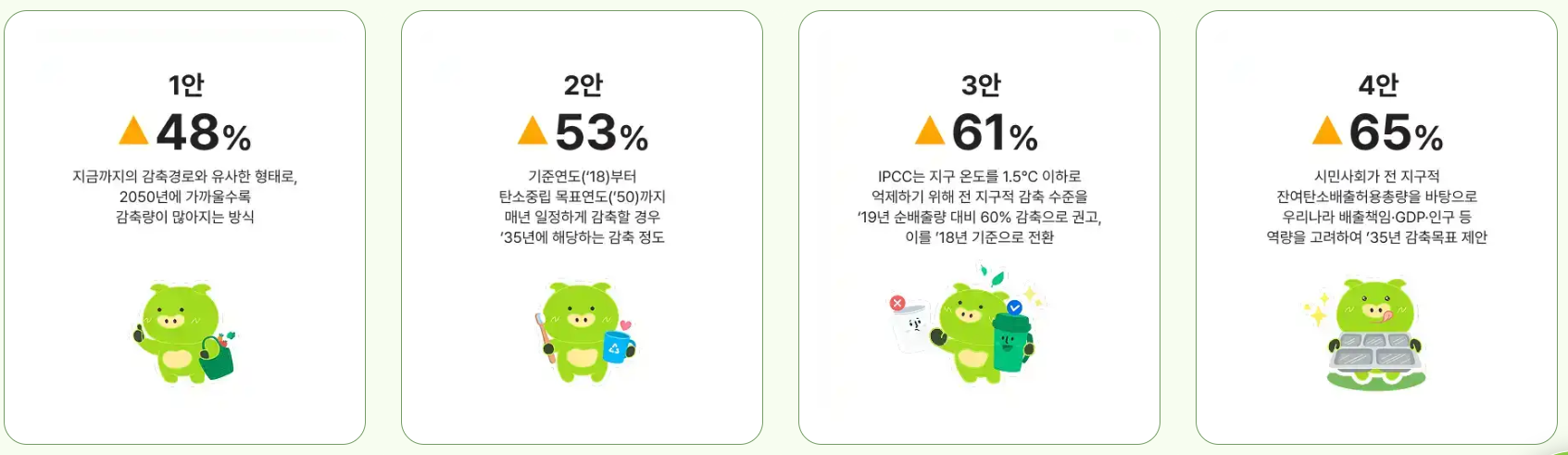

The ROK government originally presented four possible 2035 NDC scenarios, with emission reduction targets ranging from 48% to 65%. The discussion faced significant pushback from Korea’s deeply entrenched, fossil fuel-reliant industrial complex, whose representatives argue anything over 48% could jeopardize corporate survival.

South Korea, however, cannot afford to keep doing business – read: industry – as usual. According to the newly established Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment’s GHG Information Center, the industrial sector alone accounted for over 40% of Korea’s national emissions in 2024, making its decarbonization critical to making the country’s carbon neutrality aspirations even slightly feasible. The current emissions trading system (K-ETS) is already rife with loopholes which fail to hold the biggest industrial polluters accountable for their carbon footprint. Given industry’s share in domestic emissions, strong reduction targets are crucial for any NDC with real impact.

At a public hearing on November 6th, just days before the start of COP30, government officials proposed a reduction range of either 50-60% or 53-60% compared to 2018 emissions, though a finalized 2035 NDC target will likely fall on the lower end of this spectrum. A 50-53% target would be both far below what is needed and potentially unconstitutional, slowing decarbonization momentum and delaying the development of a policy and financing environment primed to facilitate a just green transition.

South Korea is expected to make its last-minute 2035 NDC announcement in a few days at the pre-COP30 Belém Leaders Summit. The decision made will signal whether the country continues to face criticism for its ongoing fossil fuel investments or takes a decisive step toward positioning itself as a leader in the energy transition across the Asia-Pacific region.

COP30: Setting the Stage for South Korea’s Coal Phaseout?

For South Korea, achieving any of its potential 2035 NDC targets requires an overhaul of its entire power sector: specifically, phasing out coal. In 2022, 39% of the country’s electricity was coal-generated, and coal still serves as a primary input in major industries like steel. Despite a gradual phasedown, coal power plants still run and have even been newly opened as recently as January 2025. Previous targets aimed to phase out coal entirely by 2050, though the current administration continues to signal a closer 2040 target date.

Progress on coal phaseout has been hindered by two major factors: greenwashing and underinvestment in renewable energy expansion. On the greenwashing front, co-firing – both biomass-related and ammonia-related - has been widely touted as an efficient means of reducing carbon emissions while retaining existing coal-based infrastructure, despite not actually solving the coal problem.

Biomass energy, burning pellets made from trees and organic matter for electricity (often alongside coal), is still heavily subsidized despite causing widespread deforestation in producing countries like Indonesia and having a carbon footprint larger than coal. The story is similar for ammonia co-firing, which the government initially planned to introduce in 24 out of 43 existing coal-fired power plants as part of its emissions reduction strategy. A recent study revealed the move could lead to a significant increase in air pollution in coal-dependent regions like Chungnam, highlighting how supposed “green solutions” would inevitably backfire while extending the lifespan of highly polluting coal infrastructure.

Can Korea Escape the Coal-to-Gas Trap?

During the recently concluded National Audit, new Climate, Energy and Environment Minister Kim Sung-hwan acknowledged this faulty narrative, affirming the most appropriate response would be to halt co-firing altogether. Concerningly, the same couldn’t be said for co-firing with liquefied natural gas (LNG), which contrary to popular belief, isn’t actually “clean”. The minister’s statement aligns with widely accepted coal-to-gas transition rhetoric which says the use of LNG can solve coal’s carbon emissions problem while bridging the gaps emerging during a transition to renewable energy. In reality, LNG’s environmental impacts remain grossly understated and underreported, making a comparison with coal essentially a pot calling a kettle black.

Korea’s ability to escape the coal-to-gas pipeline and transition directly to renewables like solar and offshore wind is hampered largely by the country’s fossil fuel-driven financial system. The money is there; it’s just being channeled to the wrong places. The problem is made worse by a slow permitting process, investor hesitation due to policy uncertainty, market discrimination and a lack of strong de-risking mechanisms. In layman’s terms, escaping the “bridge fuel” trap requires removing lots of red tape, restricting unfair systems and building investor confidence in a renewables industry that needs both public and private support.

South Korea is now under pressure to publicly commit to President Lee’s election promise of completely phasing out coal by 2040 at COP30, joining the trend of leading economies shifting away from coal. The new date would be ten years earlier than the government’s initially proposed deadline, but even so, a best-case scenario calls for coal to be phased out entirely by 2035. Environmental groups, including SFOC, have also highlighted that progress can’t stop at just a declaration, but must include a concrete, detailed roadmap outlining how a full coal phaseout will be achieved.

Adaptation Finance: A Role for South Korea?

COP30 will seek to address the question of many developing countries on the frontlines of climate change: why bother submitting new NDCs if the old ones still haven’t been financed and there are no financial resources available to ensure implementation? In 2025, the global adaptation finance gap in developing countries was between $284-$339 billion per year, compared to incoming flows of just USD 26 billion. That’s 12-14 times less money than what is needed.

To close the gap, COP29 introduced the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance, which calls on developed countries to mobilize at least $300 billion each year to fund climate action in developing countries. The long-term goal? An annual flow of $1.3 trillion by the year 2035 under the Baku to Belém Roadmap.

As one of the countries contributing significantly to global GHG emissions, South Korea is bound by the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”, meaning it has a responsibility to take a leading role in both implementing and financing climate change mitigation and adaptation. The country is home to the Green Climate Fund, the world’s largest international mechanism for climate action. Its successful operation symbolizes the ROK’s potential to play a crucial role in realizing the NCQG and making meaningful contributions to the Loss and Damage Fund and other related adaptation finance frameworks.

Looking Forward

South Korea’s moves at COP30 will determine whether it can assert itself as a regional leader in climate action and energy transition and pay its fair share for its role in climate change, or be shunned by an international community demanding more from those who have contributed the most to this crisis.

Despite the challenges ahead, South Korea’s path forward—and Asia’s broader transition—holds immense potential. The region’s technological capacity, industrial dynamism, and rising climate consciousness make it uniquely positioned to redefine what a just and sustainable transformation looks like. The coming decade can be one of decisive progress, where governments, industries, and communities across Asia turn ambition into action and cooperation into tangible climate solutions. COP30 will set the stage; it’s up to countries like South Korea to perform.

It’s with this spirit of momentum and collaboration that the Asia Climate Solutions Pavilion returns to COP30.

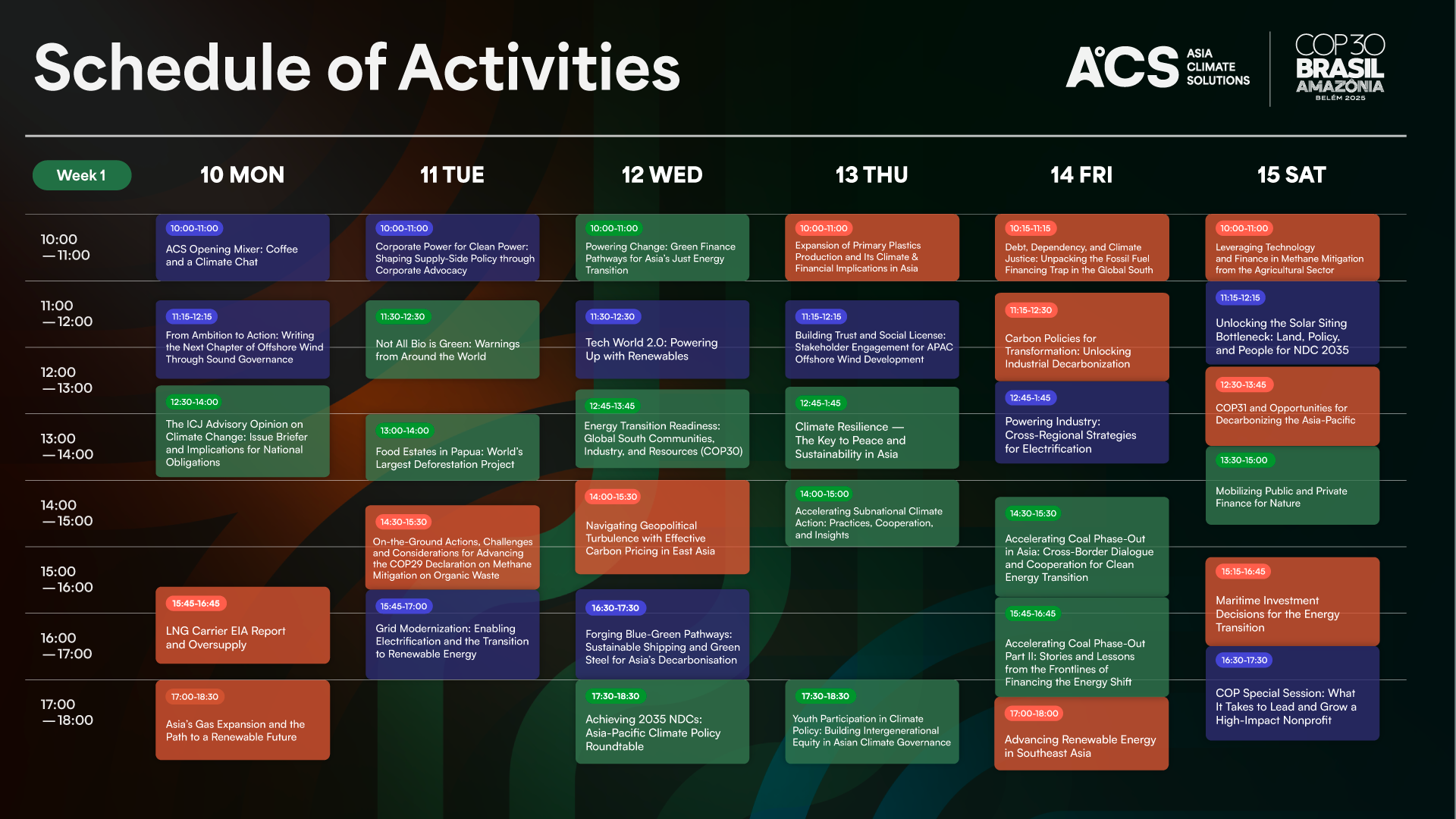

For Asia, the COP30 Action Agenda sets clear benchmarks for energy transition, climate finance, and industrial decarbonization. At COP30, Solutions for Our Climate (SFOC) will once again host the Asia Climate Solutions Pavilion, under the theme Asia: The Climate Pivot Point. This year’s pavilion will feature over 60 events hosted by SFOC and over 30 partners over a two-week period, highlighting Asia’s emerging role as a pioneering region in the global energy transition. It will serve as ground zero for invigorating conversations on the innovation, ambition and collective will needed to align efforts to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors and scale up renewables expansion across Asia and beyond.

Interested in seeing how Asia is leading the charge toward a future where energy is done differently? Visit the ACS Pavilion in the COP30 Blue Zone from November 10–21, 2025. For detailed information on how to register your attendance, visit the official ACS Pavillion Calendar.

Check out our Week One Lineup below!

Stay tuned for on-the-ground updates via SFOC’s official LinkedIn channel.