In their quest to phase out fossil fuels, governments are on the hunt for – and investing heavily in – affordable, renewable alternatives that can be feasibly scaled to meet the ever-increasing demands of modern society. Forest biomass, though often marketed as such, is not one of them.

Biomass energy is derived from organic materials like wood, agricultural residues and animal waste. Woody biomass, cutting down and burning trees, is one of the world’s oldest fuel sources. In modern times, it comes in the form of wood pellets or chips burnt, sometimes alongside coal (so-called co-firing) to generate heat and electricity. This wood typically comes from forests, many logged and clearcut to make way for fast-growing, short rotation trees cultivated specifically for energy production.

These energy plantations are on the rise in heavily forested countries, where abundant wood supply and the promise of reliable export markets drive up the scale of wood pellet production. For importing countries, an expanding biomass industry misguidedly coexists with wider efforts to transition towards renewable energy sources.

Why the Notion of “Sustainable” Biomass Doesn’t Hold Up

Forests, especially intact, minimally disturbed primary and old-growth forests, form part of the global carbon sink. It’s estimated that forests hold back more than 1°C of warming. Of this, almost 75% is accounted for by carbon stored in primary and old- growth forests. These forest types are incredibly biodiverse and home to many endangered species, far more resistant to natural disturbances like wildfires and pest outbreaks and store an estimated 30-70% more CO2 than their logged and replanted counterparts.

Consequently, this carbon stock, once lost, is essentially impossible to restore. While trees can be replanted and forests restored, when these forests are culled – whether for timber or for energy production – their ability to recapture carbon is far less than if they had been left alone. Logging for biomass also displaces Indigenous communities, fragments the local ecosystem and contributes to biodiversity loss due to the destruction of wildlife habitats, adding social and ecological concerns to the biomass sustainability question.

In response to concerns surrounding deforestation and land- use change, the biomass industry has turned to establishing certification standards aimed at delineating “sustainable” biomass sourcing. In 2013, major European bioenergy producers established the Sustainable Biomass Program (SBP), a private, voluntary biomass certification scheme which aims to “provide assurance that biomass, whether used for energy, industry, or beyond, is sourced both legally and sustainably.” The SBP focuses on certifying biomass sourcing practices among pellet producers and traders, primarily against its six standards ranging from feedstock compliance to data collection and unlike other forest certification schemes, carbon stock assessments.

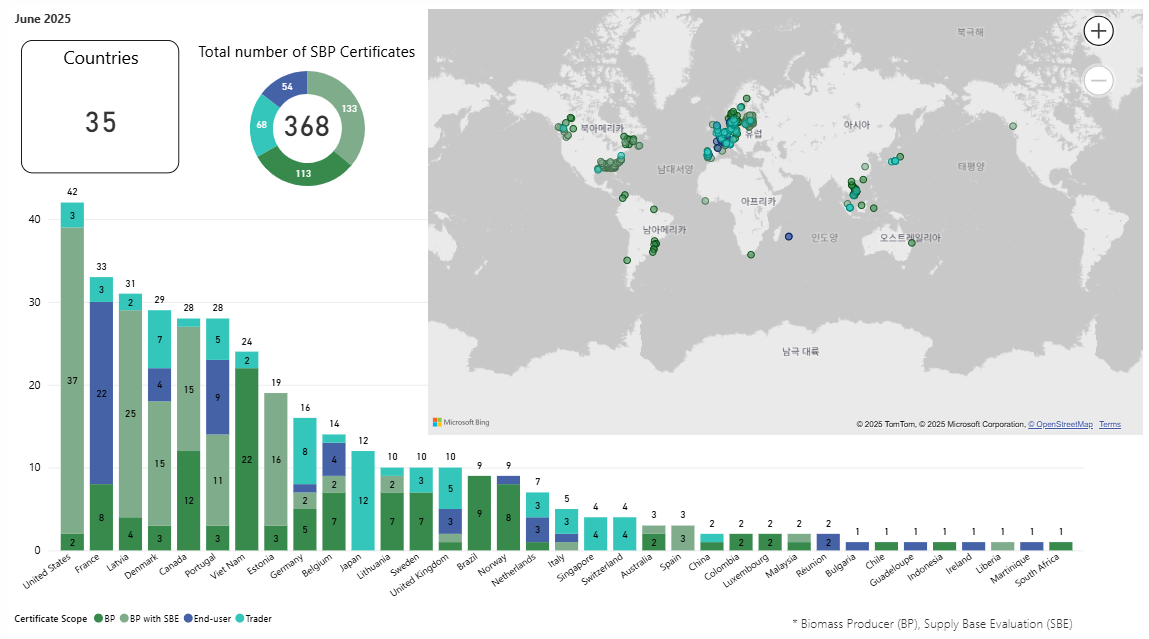

As of June 2025, the SBP certifies 368 biomass producer, trade and end user companies across 35 countries, making it the world’s largest industrial biomass certification scheme. For the year-to-date, the SBP has certified the production and sale of a combined 10.38 million tonnes’ worth of wood chips and pellets that originated mostly from Europe, the US and Canada. Most of these have been exported for energy production in biomass and co-firing power plants in Europe.

Thanks to widespread adoption and increasing government endorsement, the SBP continues to grow in popularity as a means for those in the biomass energy supply chain to ensure high yields and minimal business risks. Having the SBP certification means that biomass power plants can receive substantial government subsidies that are meant for genuine renewable energy. However, our latest joint report, Sustainable Biomass Program: Certifying the Unsustainable, reveals that the scheme is not only failing to safeguard environmental and social sustainability but also enabling forest destruction and rights violations.

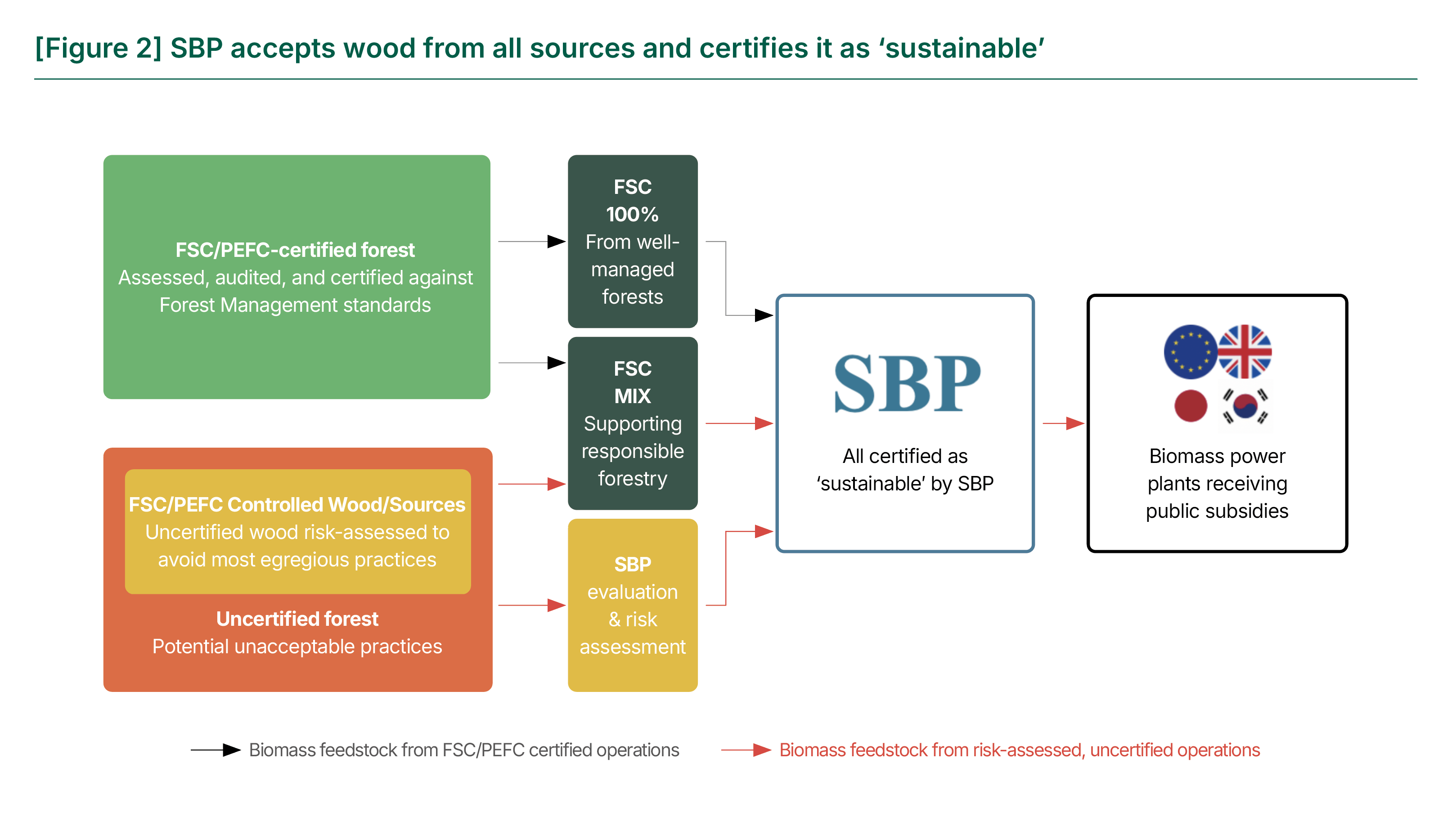

On paper, the SBP claims to ensure biomass fuel isn’t sourced from ecologically sensitive or socially contested forest areas, including primary and old-growth forests. Upon closer inspection, however, red flags start popping up. The biggest one? A lack of due diligence. The SBP relies heavily on other forest certification schemes which, despite positioning themselves as certifying responsible and sustainable forestry, all feature loopholes meant to accommodate the industry’s requests to label as much wood “green” as possible. These schemes often only rule out the most heinous of forestry practices without ensuring actual accountability for environmental impact, leaving everything else up for the biomass industry to grab and greenwash.

Our report highlights these weaknesses by dissecting the SBP’s standards and practices in a critical assessment of the scheme’s ability to effectively audit the sustainability of forest biomass. A case study of UK biomass giant Drax’s activities in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and British Columbia strips away the SBP’s heavily greenwashed façade of “sustainable”, “renewable” biomass, highlighting flaws which greenlight the logging of thousands of acres of precious forest cover each year and promote a false solution to the problem of phasing out fossil fuels.

Debunking the SBP

Certification schemes like the SBP face significant criticism due to their weak standards, and in many cases, fail to protect primary and old-growth forests. Beyond shaky due diligence mechanisms, the SBP - and the biomass industry as a whole – are propped up by bad math. Faulty carbon accounting assumes all of biomass’ CO2 emissions are accounted for when trees are cut down, completely excluding those released when this biomass is burned in power plants. When the social and ecological costs are added to the equation, the entire notion of biomass being “sustainable” and “renewable” falls apart.

Flaw #1: The Due Diligence Problem

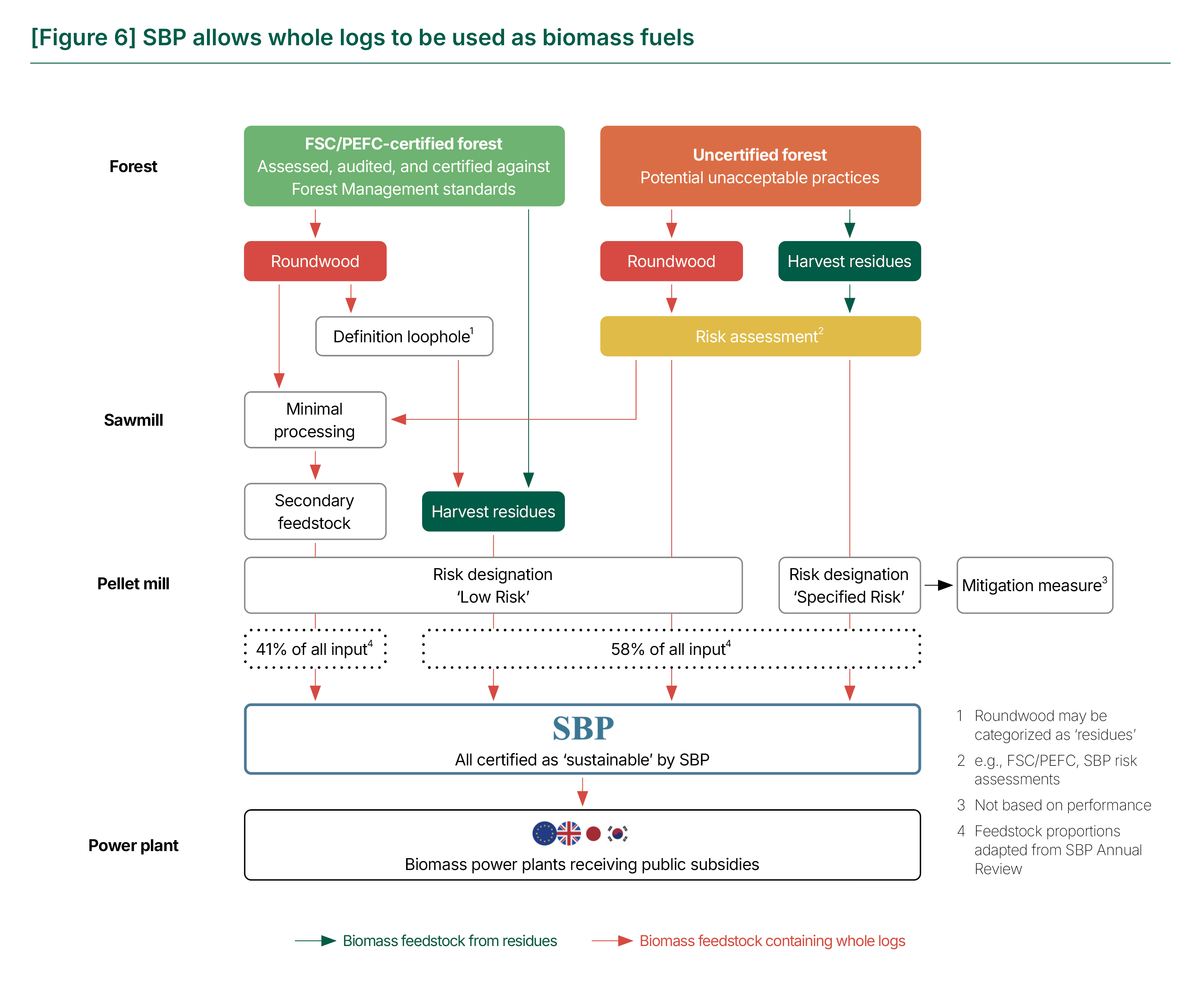

The SBP certifies wood pellet producers and traders as “sustainable” without vetting forest management practices or engaging directly with logging companies. It relies on desk-based Risk Assessments and broad screening tools that flag only the most heinous of logging practices, creating loopholes for those which are consequently cleared as “sustainable”. To complicate matters further, the SBP relies heavily on external certification systems, which often undergo only minimal risk assessment, using their lower standards to label entire biomass supply chains, even those sourced from uncertified forests.

Wood that meets the Forest Stewardship Council’s (FSC) Controlled Wood and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification’s (PEFC) Controlled Sources thresholds is counted as eligible under the SBP’s Controlled Feedstock category, despite not being an accurate measure of sustainable forest management and avoiding only the worst of forestry practices. As long as risk assessments are conducted and mitigation measures implemented (no matter how substantial), SBP counts these labels as equal to full certification, even in cases where an independent assessment under FSC or PEFC would disqualify wood from such sources.

In British Columbia, Canada, SBP sourcing decisions rely heavily on FSC’s National Risk Assessment (NRA) to certify Controlled Wood; however, the SBP but does not replicate FSC’s spatial and ecological thresholds—which are far from being adequate already—widening loopholes for pellet mills in the region to source from controversial forest areas while presenting this supply chain as sustainable.

This lack of due diligence not just opens avenues for the greenwashed logging of vulnerable forest areas but effectively weakens the integrity of the FSC/PEFC systems.

Flaw #2: The Bad Math Problem

The very idea of the SBP runs on the myth of “sustainable” biomass, stemming from outdated carbon accounting in need of an overhaul. The SBP assumes that carbon emissions from burning wood are offset by what will be absorbed by replanted forests over decades, all while 2030 Paris Agreement emissions reductions targets loom not so far in the distance. The scheme allows biomass producers to source from primary and old-growth forests and replace those high carbon stocks with far less carbon-dense monoculture plantations. In the SBP’s eye, all logging is essentially sustainable as long as such carbon loss is masked by broad regional and national averages.

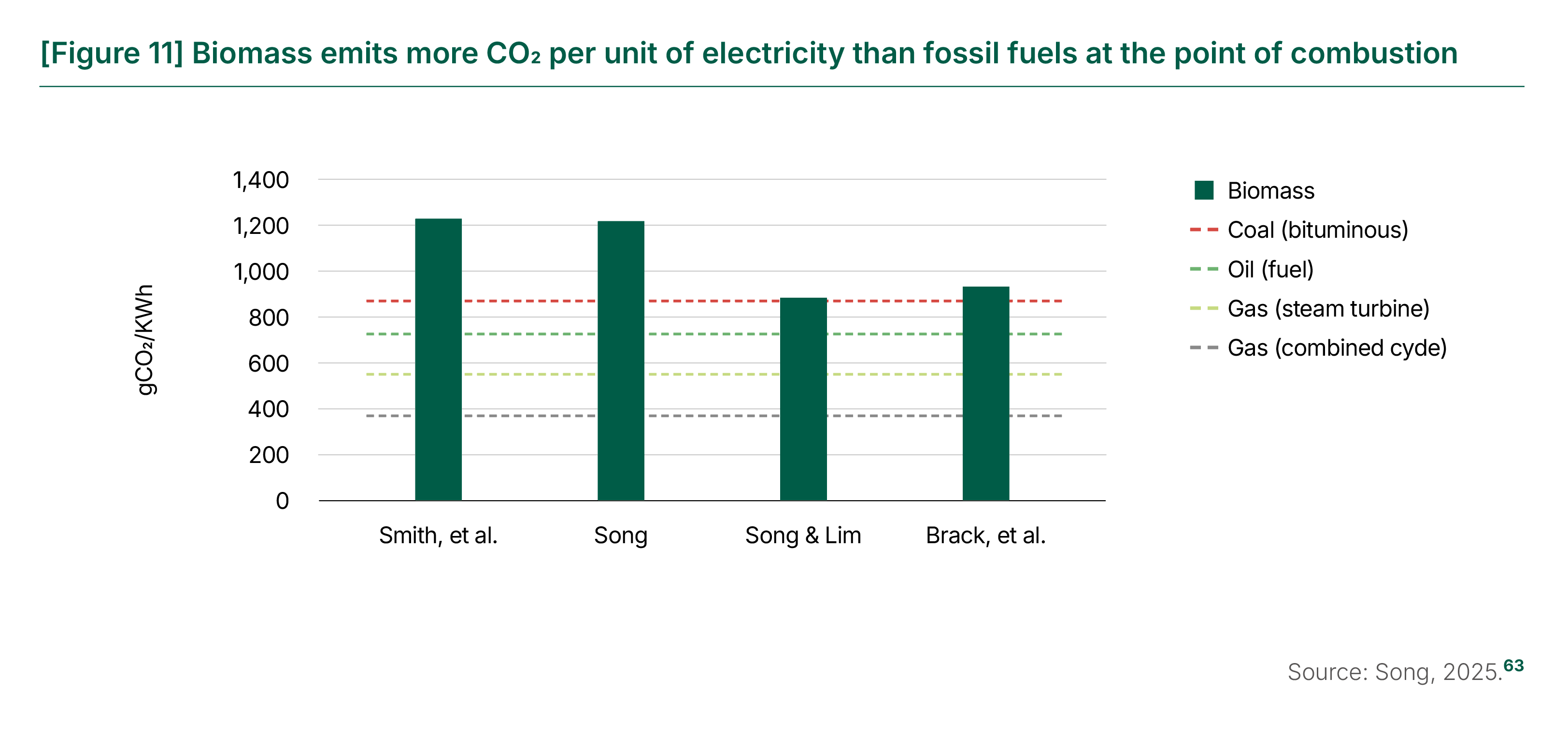

Because of these assumptions, the SBP inevitably fails at mitigating smokestack emissions – even though burning biomass emits more CO2 than coal per unit of energy produced. Thinking that biomass is automatically considered carbon-neutral in the land-use sector, the SBP tosses the responsibility for power sector emissions to energy utilities regulators. Since they too benefit from claiming “carbon neutrality” despite their actual footprint, ultimately no one is held accountable for the carbon emissions. Critics argue that the current carbon accounting regime has inadvertently created the large-scale use of biomass driving forest loss everywhere—the loophole that the SBP and the industry leverage so well to greenwash their entire premise.

Flaw #3: The People Problem

Primary and old-growth forests, beyond storing carbon and providing vital ecosystem services like flood control and water cycle regulation, are home to many Indigenous communities closely tied to the land. Overwhelmed by consultation requests from governments and companies, many of these communities often lack the capacity to engage and respond meaningfully. Under the SBP framework, which makes no distinction between a capacity deficit and a conscious, strategic silence, the absence of a response is taken as consent – but silence doesn’t equal yes.

For example, one Drax-owned pellet mill was found sourcing from unceded First Nations territory in British Columbia, an action “mitigated” by essentially outsourcing Indigenous engagement to other actors without proper consultation. This is particularly disturbing in a region which has witnessed multiple large-scale demonstrations (many led by First Nations communities) against the clearcutting of old-growth forests.

The SBP does a poor job of verifying that logging/certification operations take place only with the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of local indigenous communities. This gap in oversight inevitably undermines indigenous rights, ignoring land claims and infringing on customary territory; and no forest practice which leaves room for HR violations can be considered truly sustainable.

Flaw #4: The “Anything Goes” Problem

SBP’s due diligence issues have a spillover effect, which manifests in the practice of essentially treating (and certifying) wood from all sources as “sustainable”, regardless of their actual origin. SBP permits sourcing from logged or fragmented portions of intact forest landscapes (IFLs) once not formally protected, and unlike FSC, requires no mitigation efforts beyond IFL boundary documentation, exposing them to further exploitation.

“Forest residues” and related byproducts are treated as low-risk by default, marking them SBP-certified even when sourced from primary forests if they first pass through other timber mills. This faulty framework allows for whole logs – rather than just forest residues – to be harvested for biomass energy production. This lack of oversight refutes the industry claim that biomass energy merely utilizes leftover residues while concealing the true scale of environmental damage that follows this kind of sourcing.

In essence, the SBP creates a free pass for regulators and utilities to fulfill their reporting obligations and ‘sustainability’ quotas without actually being held accountable for the environmental damage they leave behind. In an unsurprising twist, the “Sustainable” Biomass Program is anything but sustainable. It endorses questionable industry practices that fail to meet the standards of other sustainability certification schemes while publicly doubling down on “the promise of good biomass” – a fallacy long disproven.

Let’s Recap.

The entire premise of the SBP runs on the idea of sustainable biomass, which…just isn’t a thing. Widely endorsed as a “carbon neutral” alternative to fossil fuels, the biomass industry’s carbon footprint dovetails with this claim. Under certification schemes like SBP, countries importing wood pellets get to claim they’re pursuing “clean” energy, while producing countries sit rife with certification and oversight issues, inevitably fuelling deforestation and land-use change. Biomass plantations replace large expanses of forests, fragmenting wildlife habitats, reducing biodiversity and displacing Indigenous communities.

The SBP is supposed to ensure the biomass feedstocks certified in their name pass the sustainability test and are free of ties to these issues. However, voluntary schemes like SBP and related forest certifications have a structural issue - leaving the biomass industry to regulate itself with dodgy reporting and very little accountability for deforestation. Worse still, despite these critical flaws, the mainstream acceptance of the SBP framework is a means to justify continued investment in a biomass industry long criticized for its environmental impact. It’s greenwashing at its finest – and the world’s forests are paying for it.

The Global Implications of Doing Nothing

Our latest report highlights the weaknesses of the SBP framework through a case study conducted in the Canadian provinces of BC and Alberta. If logging from controversial sources can still slip under the radar in Canada, known for having some of the world’s strongest forest governance, things aren’t looking good for biomass exporting countries with far less rigorous regulation.

Legal loopholes in Indonesia made way for the intensive clearing of tropical rainforests for biomass plantations, while native forests in Chile have been replaced by monoculture plantations, often without FPIC from local Indigenous communities. In Malaysia, pellet suppliers forced to withdraw from the FSC over illegal logging, deforestation and Indigenous rights violations are still certified sustainable under the SBP due to a lack of rigorous independent assessment.

As governments around the world continue to endorse the SBP, the greenwashing of the continuous exploitation of ecologically fragile and socially contested forests while promoting a narrative of sustainable biomass will continue.

Looking Forward

As the climate and biodiversity crises intensify, the need to combat industrial deforestation and its social and environmental consequences is greater than ever. Large-scale biomass isn’t – and has never been – a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels. The world has returned to a pre-industrial fuel source that’s impossible to scale to demand, let alone sustainably – and the deeply flawed SBP is being used to justify subsidizing this futile endeavor.

At first glance, there is little that can be done about forests already exploited under SBP-greenwashed biomass certification systems. At the same time, there are urgent steps that must be taken by both governments and forest certification schemes like the FSC and PEFC to protect what's left.

For starters, governments must dispel the notion that biomass is carbon-neutral; it is not, and no amount of creative math will change that fact. They must hold biomass producers and end users accountable for smokestack emissions, not simply assume replanted forests can recapture lost carbon previously stored for centuries.

Mandating thorough, independent auditing of forestry practices in a manner that promotes transparency and accountability can actively employ human rights and environmental due diligence. Leaving certification up to an industry-led body eager to find loopholes and dodge restrictions has to go.

Most importantly, governments must roll back biomass subsidies and restrict the industry’s access to green finance. Burning wood for energy is not cheap; the biomass industry exists only because governments are pouring in billions in subsidies every year to prop up the otherwise stranded business. Taxpayers’ and bill payers’ money should be spent on protecting the forests, not destroying them.

Furthermore, forest certification schemes like the FSC and PEFC also have a responsibility to ensure their frameworks are not being used to greenwash unscrupulous sourcing practices in already vulnerable forest ecosystems. This may require extensive reform of the loophole-rich Controlled Wood and Controlled Sources thresholds, restricting industry players from using them as stand-ins for actual certification. Such reform, of course, can only come from acknowledging that we simply cannot scale up biomass production at current demand rates and preserve the integrity of the forests we have left.

The Bottom Line

At today’s rate of warming, the planet can’t wait decades for forests to regenerate and recapture lost carbon. The urgency must be on stopping new carbon losses, especially from biomass industry-driven deforestation. The SBP’s “promise of good biomass” is a costly misconception that is co-opting the investment and political will necessary to facilitate a transition to genuinely renewable alternatives to fossil fuels.

On the current trajectory, forests across the globe are at risk of becoming net carbon sources rather than sinks, pushing us towards climate change tipping points that the planet may not be able to recover from. Natural forests, especially old-growth and primary forests like those in Alberta and British Columbia, may be some of our last standing soldiers in the battle against a warming climate. We cannot afford to keep dressing up deforestation with forest sustainability certification schemes that don’t actually protect them. Putting forests on the (literal) chopping block in the pursuit of not-so-clean energy – slapping a pretty “SBP-certified” label on in the process” – is not a luxury this planet can afford.