In This Edition:

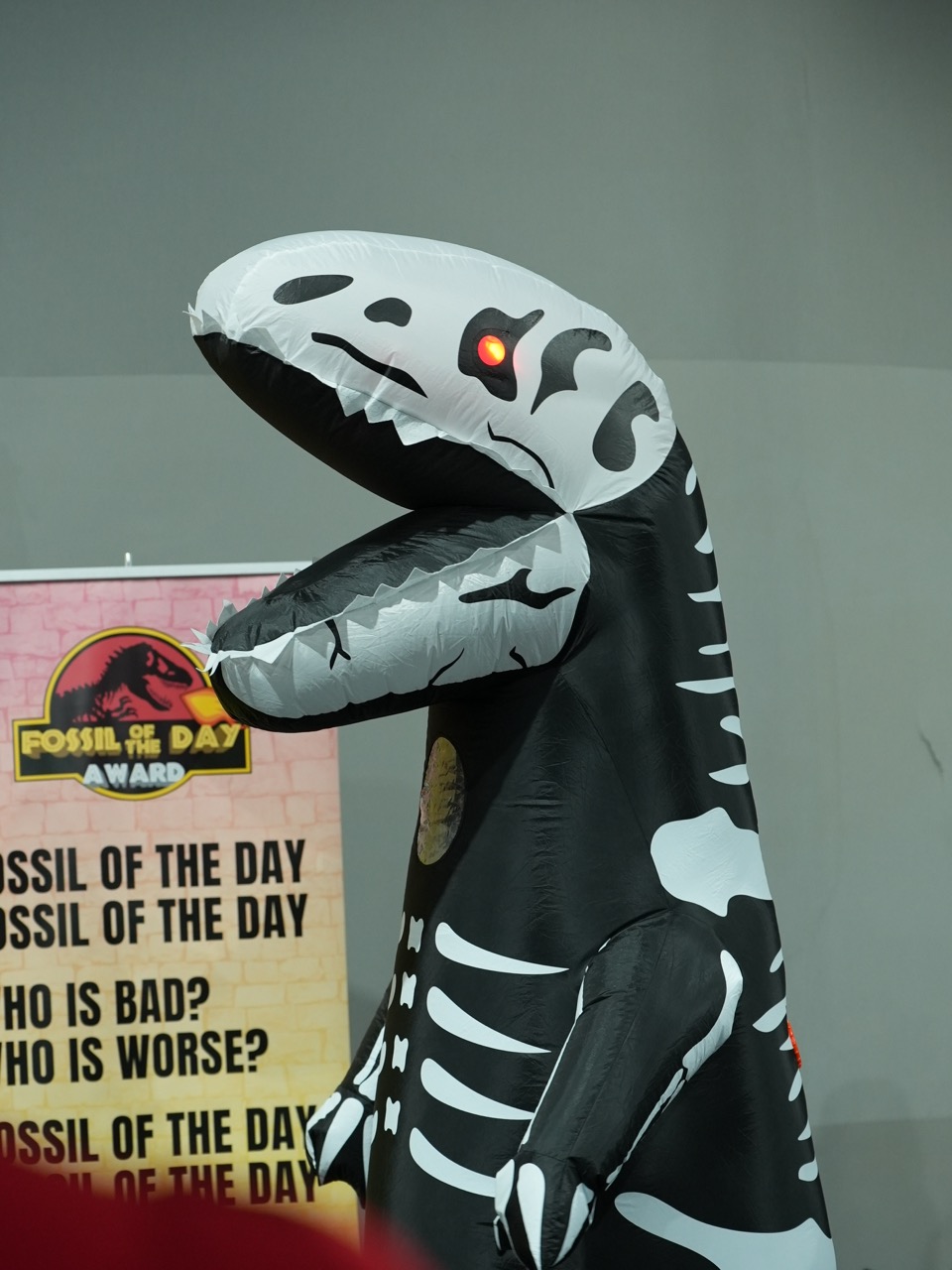

COP30’s long-anticipated Global Mutirão package delivers a mixed bag of results, with mentions of fossil fuel phaseout completely absent from the final text.

Indigenous peoples and civil society voices call out a “People’s COP” undermined by incidents of state-led repression and lip service on inclusion in decision-making.

Brazil and Columbia set the tone for independent, coalition-based action to address fossil fuels amid UNFCCC negotiation breakdown.

Türkiye and Australia strike a shaky deal on COP31 hosting rights, with the fate of Pacific SIDS left hanging in the balance.

A COP for the Books

This year’s UN Climate Change Conference, taking place at the edge of the Brazilian Amazon, set out with high hopes, aiming to restore faith in a multilateral system under unprecedented pressure at a moment where climate action is needed more than ever. Two weeks later, the curtain has finally come down on COP30, colored by novel initiatives, last-minute deadlocks, extreme weather, a sudden fire and civil society pushback.

Highly anticipated calls for an official roadmap to phase out fossil fuels – a core part of addressing the climate crisis – went unanswered in the final Global Mutirão Decision. It’s the latest strike for those long disillusioned with the UN climate process, where the hunt for “consensus” far too often cripples real commitment.

Yet, there are silver linings. More and more, countries are seeking to deliver palpable climate action, both in and out of the increasingly turbulent UNFCCC process. The momentum built in the sweltering corridors of COP30’s Blue and Green Zones is bubbling over, and real action is taking shape.

In our fourth edition of the ACS newsletter, we unpack the COP30 outcome package: what it delivered, what it didn’t, and what it means for the future of climate negotiations.

Unpacking the Global Mutirão Package

For the uninitiated, the non-binding final texts that follow every COP are about compromise that often turn what countries should do into what they could do if they subscribe to the idea of meaningfully addressing the climate crisis. Generating consensus across 194 Member States with widely varying national priorities is, naturally, a daunting task that often requires significant trade-offs which often weaken the effectiveness of a text meant to guide global climate action. Results like the universally adopted Montreal Protocol and the Paris Agreement are rare anomalies.

The Brazilian Presidency dubbed this year’s COP a “Global Mutirão”, bringing together stakeholders from all walks of life in an admirable attempt to address the implementation disease plaguing global climate negotiations. Justice, inclusion and shared responsibility were underrunning tenets of the “implementation COP”, where civil society and Indigenous representation surged and pressing issues of adaptation finance and fossil fuel phaseout took center stage. The goal? A people-centered, planet-focused COP that delivered tangible, legally binding action on mitigation and adaptation while addressing the blatant imbalances hindering those on the frontlines of climate change from taking it .

The “Global Mutirão” was expected to tackle “the big four”: scaling up adaptation finance, measuring progress towards the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), aligning climate action with the 1.5°C goal, and addressing unilateral trade measures. The Brazilian Presidency’s Action Agenda served as a novel, comprehensive approach to streamlining multistakeholder action to speed up emissions reduction, climate adaptation and facilitate the transition to sustainable economies. The COP30 agenda also gave unprecedented attention to deforestation, biodiversity conservation, and Indigenous representation in decision-making spaces, taking advantage of the conference’s location on the edge of the Brazilian Amazon.

Despite concerns surrounding the logistics of hosting the world’s largest climate gathering in Belém, one of Brazil’s poorest, most underserved cities, the COP30 Presidency stood firm in its ambition to deliver a COP with a difference.

Our verdict? Brazil has succeeded; just not in the ways most of us expected.

Here’s how it all went down.

Adaptation Gets a Boost…but at a Cost

Developing country calls for a tripling in adaptation finance did eventually make it into the final Mutirão text, with some caveats. The new goal replaces the 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact’s call for countries to double finance flows by 2025, aiming to triple them by 2035 compared to an undefined baseline year. Compared to original proposals of 3x adaptation finance by 2030 compared to 2025 levels, the COP30 target is both delayed and unclear — factors those on the frontlines may not have the luxury of bracing for.

The outcome document did call on countries to “urgently advance actions” to scale up adaptation finance to $1.3 trillion per year in line with the Baku to Belém Roadmap, though it expresses concern over a persistent shortfall in contributions to and continuous disputes over the governance of the Adaptation Fund, which aims to raise at least $300 billion each year to finance adaptation in developing countries. Discussions also included increasing the resources of the Loss and Damage Fund and the Green Climate Fund.

At the heavy cost of a deep split through the middle of the G77+ China coalition, countries eventually agreed on a list of 59 progress indicators tied to the Global Goal on Adaptation, out of a targeted 100. Critics say the selection process was far from transparent, with some pushing back against a truncated list of indicators they term “intrusive” and under-negotiated. Others say without sufficient adaptation finance, many of the adopted indicators lose efficacy altogether.

National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) got a passing grade on progress, with the final text highlighting the importance of integrating gender-responsive, IPLC-informed, nature-based and ecosystem-oriented approaches into NAP implementation.

Trade Makes it into the Final Text

In another first, the Mutirão decision also called for the implementation of three annual dialogues on trade and “reaffirms” that unilateral climate action measures should not include “trade restrictions that are “arbitrary” or “discriminatory”. This was backed by the Presidency’s announcement of a consultation process calling for government and civil society input into the proposed Integrated Forum on Climate Change and Trade (IFCCT), set to take place in Geneva this December.

Silver Linings: The COP30 Action Agenda

Where substantial negotiations faltered, progress towards the 30 key objectives outlined under the COP30 Action Agenda proved far more fruitful, producing around 120 Plans to Accelerate Solutions covering mitigation, adaptation and means of implementation across multiple sectors, from agriculture and food systems to transport and industry to forest, ocean and biodiversity conservation. It marked a notable shift from pledges to voluntary, country-owned initiatives which can be developed and implemented outside of the arguably limited UNFCCC process, speeding up climate action amid geopolitical turmoil.

Highlights included the launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), a blended market-based mechanism designed to incentivize forest-rich countries to preserve their standing forests and recognize and compensate frontline Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) for their critical role in forest conservation. Another early outcome was the Belém 4x Pledge on Sustainable Fuels, which aims to quadruple the use of sustainable fuels by 2035, though critics warn expanding biofuel and biogas production runs the risks of worsening deforestation, food insecurity, and large-scale land conversion.

Other developments included the introduction of a $300 million-backed Belém Health Action Plan, the RAIZ Accelerator, a new initiative aimed at restoring degraded farmland to strengthen food security and the Fostering Investable National Planning and Implementation (FINI) initiative, which aims to deliver $1 trillion for adaptation projects by 2028. Other sectors like methane were highlighted through initiatives like the No Organic Waste (NOW) Plan, which aims to cut methane emissions from organic waste by 30% and integrate 1 million workers into the circular economy by 2030. Subnational governance was also among them, with COP30 publicly announcing the Plan to Accelerate Multilevel Governance (PAS), designed to embed local leadership in 100 NDCs by 2028.

Fossil Fuels Omission Undermines 1.5°C Realignment Gains

The Global Mutirão became the first COP outcome document to formally acknowledge the likelihood of a 1.5°C overshoot, presenting two broad initiatives aimed at limiting its duration and impact. The conference also addressed the significant emissions gap, urging countries to strengthen their next round of NDCs to align with the Paris Agreement goal. The vaguely defined “Global Implementation Accelerator” (GIA) and “Belém Mission to 1.5” were introduced as voluntary frameworks designed to strengthen implementation of NDCs and NAPs while “keeping 1.5°C in reach”, calling on countries to step up to the plate. This inherent ambiguity was made worse by the eventual omission of any references to fossil fuels in the final Global Mutirão text, even after overwhelming support for a practical, legally binding roadmap to transition away from their use.

Days of momentum building towards what should have been an unprecedented, explicit acknowledgement of the role of phasing out fossil fuels in mitigating climate change ultimately culminated in a lowest common denominator deal that barely managed to be endorsed by petro-states like Saudi Arabia, Russia, India and the Arab Group, for whom the issue remains a dealbreaker. The decision has driven significant criticism from now over 90 countries (some themselves earning significant revenue from fossil fuels) which, under Brazil’s lead, agreed to work towards a formal roadmap to Transition Away from Fossil Fuels (TAFF). Pressure to avoid a veto led resulted in failing to address the fossil fuel problem beyond vague references to COP28’s Global Stocktake (which, ironically, doesexplicitly call for a fossil fuel phaseout), inevitably jeopardizing the perceived legitimacy of the entire outcome document.

A People’s COP on (and Under) Fire

COP30 continued the resurgence of civil society participation that began in Baku after years of repression, with the Brazilian Presidency committing to increasing the representation and participation of Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) in official negotiations. Over 5,000 people sailed into Belém as part of a flotilla coalition of Indigenous groups, frontline communities and climate activists headed to the concurrent People’s Summit, where they sought to center the Amazon, its protection and its people in key discussions.

While COP30 did produce some wins for these communities, like the recognition of the official territory of the Kaxuyana and the Circle of Peoples which sought to integrate Indigenous and traditional knowledge into the COP agenda, the bigger issue of representation in high-level negotiations remained unresolved. Despite well-intentioned promises to amplify the voices and protect the rights of IPLCs, COP30 managed to further erode trust in the UN process thanks to a combination of UN-sanctioned suppression attempts, comparatively minimal access to the decision-making process and lip service paid to their calls for a fossil fuel phaseout. Investigations later revealed that of more than 2,500 Indigenous representatives present, only 360 were granted access to the Blue Zone, a figure that paled in comparison with the more than 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists later identified among COP30 delegates, many attached to official country delegations. This blatant disparity undermined the small victory of the first ever explicit reference to the rights of IPLCs in a COP outcome document.

While COP30 may have set the stage for the largest gathering of these communities in recent COP history, this increased visibility has not significantly influenced the negotiation outcomes of a process Indigenous leaders say continues to promote false solutions, commercialize nature and legitimize a fossil fuel-based status quo.

Taking Stock of the “Implementation” COP

In omitting concrete mentions of the need to phase out fossil fuels, COP30 has delivered a bare minimum package that appears to have prioritized shaky consensus over real climate action. In contrast with the Brazilian presidency’s widely lauded approach to this year’s negotiations, the Global Mutirão decision fails to address the elephant in the room, weakening its legitimacy and its effectiveness. Hard-won “wins” on adaptation finance, just transition and realigning climate action with the 1.5°C target lose their shine when one considers none of those goals can be truly achieved without a fossil fuel phaseout.

COP30 has been subject to much of the criticism of its predecessors: what’s the point of spending billions to construct venues and flying tens of thousands of people across the world each November if after more than three decades, clearly evidenced solutions to mitigating the climate crisis continue to be backspaced into oblivion by the need for consensus?

It’s no secret that a climate process involving sovereign states with competing national interests on a historically uneven playing field will have its limitations; it comes with the territory. But at a point where science, technology and traditional knowledge are pointing towards increasingly feasible, scalable paths to achieving development, energy security and economic growth without sacrificing the planet, it’s no wonder outcomes like COP30’s have made many believe the UNFCCC’s annual conference has outlived its usefulness.

Yet, where a broken UN process has delivered consensus at the cost of true action, countries have taken matters into their own hands. Multilateralism, contrary to popular belief, was indeed alive and well throughout COP30, with parties managing to avoid a complete breakdown in negotiations despite significant delays and disagreements. Indigenous and civil society voices were loud and relentless, keeping even the COP30 President on his toes. More than 90 countries combined, including host country Brazil, committed to tackling the fossil fuel and deforestation problems head-on, with or without the UNFCCC’s blessing. In the midst of resurging nationalism, institutional fatigue and deep division, is this not the very spirit of multilateralism, the very idea of “stronger together” in action?

COP30 provided a platform for a growing, civil-society backed coalition of countries scattered across the development and climate vulnerability spectrum to challenge the fallacy that cross-border, large-scale climate action can only be conducted – and mandated – through the UNFCCC process, á la the Paris Agreement. Colombia’s announcement of the inaugural International Conference on Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels in April 2026, co-hosted by the Netherlands, may be the start of a wider shift where countries are taking the lead in doing what the UN system cannot. Similarly, the Brazilian Presidency’s public commitment to ensuring the launch of and progress on implementation towards roadmaps to phasing out fossil fuels and ending deforestation demonstrates a mindset change which now sees climate action as not simply a moral obligation, but a country-owned responsibility that must be fulfilled even when multilateral systems fail.

And for all intents and purposes, that is, in fact, a win.

So…What Now?

In the ashes (some of them literal) of COP30, a more than yearlong standoff between Turkiye and Australia has ended in a fragile arrangement which will see the former host next year’s climate negotiations in its resort city of Antalya, while the latter will assume the Presidency and oversee key negotiations and the COP31 Action Agenda. The news is a big blow to low-lying Pacific SIDS, whom had been promised a leading role in negotiations had Australia secured hosting rights, though parties have agreed to host the Pre-COP in the Pacific.

In the meantime, eyes will be on those countries which have taken up the mantle of ensuring progress on phasing out fossil fuels, to assess whether their pledges can truly deliver results where the UNFCCC process has been crippled. Pressure will also be on countries yet to submit their 2035 NDCs, alongside expectations for comparatively weak, but existing NDCs to be fully implemented, achieving the at least 12% reduction in GHG emissions predicted by the latest NDC synthesis report. Civil society, Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) will, of course, have their own part to play in maintaining the momentum gained during COP30, whether by generating public pressure on governments, conducting research and sharing expertise that can help accelerate the energy transition, or ensuring traditional knowledge and livelihoods of marginalized communities are not sidelined in the name of sustainable development.

Parting Thoughts

Despite its failures and disappointments, COP30 still marked a notable shift in the general consensus on how the world goes about addressing the climate crisis, driving sovereign states to act – and to do so together - when the system underdelivered. Individual governments, informal coalitions and Indigenous-oriented civil society movements are the new protagonists of the multilateral climate arena, driving momentum, maintaining pressure and actualizing solutions, undaunted by the weakened UN system in which they converge. This fact, in and of itself, is exactly why spaces like COP must continue to exist – albeit in a far more effective form.

COP30 showed us we do, in fact, have what it takes to do global climate action differently.

The challenge, as it has always been, is to deliver.